We've a ways to go, but it seems a lot more likely than it did yesterday.

I'll withhold judgement until I've had some time to digest specifics, but the broad strokes of this look promising, and it would appear the White House is on board.

Glad to hear that some Republicans (in the Senate at least) seem to have found a new top political priority.

1.28.2013

1.22.2013

science journalism isn't political journalism

Or it least it oughtn't be, argues Zack Beuchamp:

What’s particularly galling about The Daily Beast‘s vaccine “debate” is that it treats science criticism like punditry. Political writing is plagued by a consensus of bores, commentators who all have opinions within the same narrow band of “acceptable” views...

Science journalism has, if anything, the opposite problem. The basic task of a science journalist is to explain complicated scientific findings to people who don’t have the time or the expertise to learn it from primary sources. Increasingly, science journalists are acting as science critics as well as science expositors, but that doesn’t undermine the need to fully understand and embrace scientific methodology (if anything, it intensifies it). Science journalism, sadly, often fails in both of these roles. This generally happens when writers lack the time or background knowledge necessary to properly digest and explain the research in question...

By setting up vaccination as an issue up for debate in the same way that political questions are, the Beast articles can leave a reader who isn’t aware of the overwhelming scientific consensus might simply throw up their hands (as happens in the climate debate) and say “who knows whose research is right?” But that’s not how it is. People who conclude that there’s a real case that the flu vaccine might do more harm than good are less likely to get flu vaccines, for them or their family. That makes people more likely to get sick and, possibly, die. There isn’t any real debate about this among epidemiologists. This should be settled.

1.21.2013

some things never change

If I have any lingering regrets from the election of 2008, it's that we missed out on the spectacle that would have been Bill Clinton's tenure as First Lady.

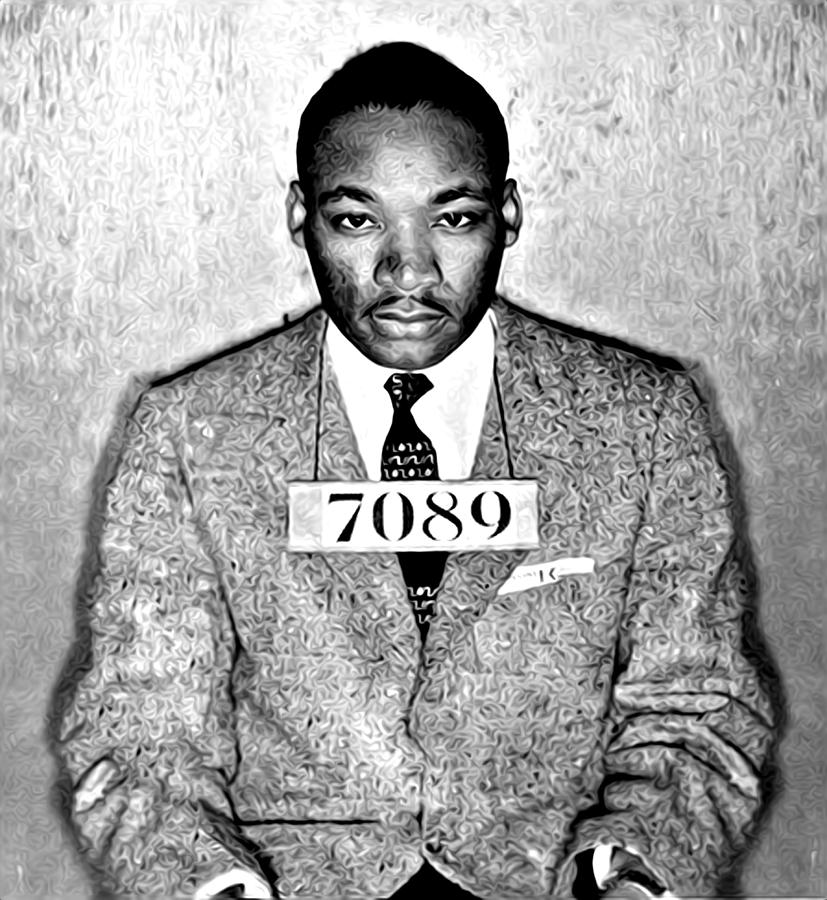

"You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court's decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us consciously to break laws. One may well ask: "How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?" The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws."As they say these days...read the whole thing.

1.16.2013

back of the envelope: handguns and the marginal homicide

[Ed: I actually started writing this a couple of weeks ago, and had to set it aside to work on other things. In light of the president's policy proposals today, which seem to consist of mostly toothless executive orders and lobbying for congress to reign in assault weapons and large magazines, I think it's worth putting out there even though it's not as fully formed as I would like. Especially since I find myself in the--admittedly familiar, at this point--position of both being revolted at the reactionary pro-gun rhetoric and of the opinion that what the president is proposing is likely a waste of time and resources.]

Let's dispense with the rhetoric for a moment, and look at some numbers.

I came across the following on Wikipedia while looking for something else. It's from a data set produced by the Bureau of Justice Statistics breaking down homicides in the US by the weapon of choice. Here's the graph that appears on Wikipedia:

The obvious point here is that handguns account for the majority of homicides in the US. But what I find interesting is that homicides involving other weapons have remained very nearly constant (knifings having experienced a small, but steady drop) over the the 30-year time period measured, while handguns appear to account for the relatively huge fluctuations in year-over-year homicide rates. Just to be sure, I plugged the numbers (which you can get in table form here) into my own spreadsheet, and added a column for total homicides. What you get is this:

In other words, handgun homicides drive the overall rate. Just to drive the point home a little more formally:

Now. None of this tells us anything about why homicide rates are higher or lower in any given year. Nor do they (necessarily) explain why the rate in the US is so much higher than other western countries.

However, I do think it is fair to argue that the marginal homicide in the US is--statistically speaking--committed with a handgun, because again: note that the rates of homicides by other means are really, really stable year over year. Put another way, the difference between a homicide and a non-homicide may very well be in many cases, having a handgun with which to commit it, or not.

Whatever your predisposition is regarding guns, public funding for mental health services, criminal justice policy, or any of the other arenas of debate that impinge on the question of gun violence in America, I should hope it is safe to assume that everyone is interested in having fewer people die violent deaths. The points of contention, really, aren't about the ultimate goal, but rather 1) how best to achieve that goal, and perhaps 2) how one weighs the trade-offs involved in policies pursuant to achieving that goal.

Too often--and especially after high-profile mass shootings--the argument is made that "nothing could have prevented this." This is problematic, not because it is untrue in many of those particular cases, but because it tends to lead to the--perhaps unconscious--conclusion that all homicides are therefore not preventable. Clearly, no one seriously believes this; if every homicide (or indeed any crime) is an utter inevitability, why bother having a criminal justice system at all? And yet it seems an article of faith among many in this country that all efforts to reign in our culture of gun violence via tighter regulation of guns are ultimately futile.

That said...it is entirely fair for gun rights advocates (or anyone) to demand a measurable positive return on a change in policy, particularly a policy that abridges (or that they consider to abridge) their own personal freedom (see point #2 about trade-offs above). And if the metric we are using to evaluate that positive return (or lack thereof) is the total homicide rate, I'm not sure that it makes sense to fret too much about assault weapons or large magazines.

If we're serious about reducing total homicides via reducing the number and/or types of weapons in general circulation, it makes a great deal more sense to go after handguns. Given the number of people that own handguns in this country, that is naturally a much more difficult proposition.

Let's dispense with the rhetoric for a moment, and look at some numbers.

I came across the following on Wikipedia while looking for something else. It's from a data set produced by the Bureau of Justice Statistics breaking down homicides in the US by the weapon of choice. Here's the graph that appears on Wikipedia:

In other words, handgun homicides drive the overall rate. Just to drive the point home a little more formally:

Now. None of this tells us anything about why homicide rates are higher or lower in any given year. Nor do they (necessarily) explain why the rate in the US is so much higher than other western countries.

However, I do think it is fair to argue that the marginal homicide in the US is--statistically speaking--committed with a handgun, because again: note that the rates of homicides by other means are really, really stable year over year. Put another way, the difference between a homicide and a non-homicide may very well be in many cases, having a handgun with which to commit it, or not.

Whatever your predisposition is regarding guns, public funding for mental health services, criminal justice policy, or any of the other arenas of debate that impinge on the question of gun violence in America, I should hope it is safe to assume that everyone is interested in having fewer people die violent deaths. The points of contention, really, aren't about the ultimate goal, but rather 1) how best to achieve that goal, and perhaps 2) how one weighs the trade-offs involved in policies pursuant to achieving that goal.

Too often--and especially after high-profile mass shootings--the argument is made that "nothing could have prevented this." This is problematic, not because it is untrue in many of those particular cases, but because it tends to lead to the--perhaps unconscious--conclusion that all homicides are therefore not preventable. Clearly, no one seriously believes this; if every homicide (or indeed any crime) is an utter inevitability, why bother having a criminal justice system at all? And yet it seems an article of faith among many in this country that all efforts to reign in our culture of gun violence via tighter regulation of guns are ultimately futile.

That said...it is entirely fair for gun rights advocates (or anyone) to demand a measurable positive return on a change in policy, particularly a policy that abridges (or that they consider to abridge) their own personal freedom (see point #2 about trade-offs above). And if the metric we are using to evaluate that positive return (or lack thereof) is the total homicide rate, I'm not sure that it makes sense to fret too much about assault weapons or large magazines.

If we're serious about reducing total homicides via reducing the number and/or types of weapons in general circulation, it makes a great deal more sense to go after handguns. Given the number of people that own handguns in this country, that is naturally a much more difficult proposition.

1.08.2013

eating in mexico city (a completely subjective and non-exhaustive guide)

Upscale

There are a lot of fancy restaurants in Polanco, the upscale neighborhood where you will find international 4- and 5-star hotels and wealthy tourists. I am sure that many of them produce excellent food. We ate at one of them, which I will not name because I really have no desire to trash them (they delivered exactly what they promised, well, and the service--while a bit overly fussy for my tastes--was excellent.)

My beef is that I've had essentially the same genre of food, slightly better--and less expensive--in several restaurants in Tucson, and particularly at Cafe Poca Cosa. This suggests to me that high-end Mexican can only be so good, and I might have had it already. Good to know...back to the taqueria we go...

On our last night, however, we did treat ourselves to the more affordable (but still a bit pricy by Mexico City standards) La Tecla in Roma. This was excellent, and I would rank it among my favorite dining experiences in Paris, Saigon, Hanoi, Chicago, etc., etc. We had a tostada with sashimi-grade tuna, caramelized onion, and chipotle mayonnaise that was to die for. I had a steak with twin sauces of stilton and huitlacoche (don't knock it till you've tried it), and M had a fish dish; both were solid. Dessert (which I didn't even bother ordering at the other place) was an impossibly airy flan with cajeta sauce and a boozy crepe dish with a bunch of berries set on fire at some point. Awesome.

Cantinas

The cantina is probably the thing that your "standard" Mexican restaurant in the US is most trying to recreate--casual places with big tables, wandering mariachis, reasonably priced food, and they don't mind if you linger for hours playing dominoes and drinking beer. However, you are unlikely to hear the words "careful, hot plate!" and not everything comes entombed in processed cheese.

We ate at two cantinas--one of which I cannot recall the name of, but it is the one the southeast corner of Obregon and Cuauhtemoc [Ed: per my wife it is called La Autentica]--and at El Centenario near the heart of the Condesa neighborhood. But the one we really loved was La Opera between the Zocalo and the Alameda. (We just had drinks there.) That place was like stepping back in time.

Tacos and tortas

You can't go far in Mexico City without tripping over a small place that sells tacos and/or tortas (usually both). As far as I can tell, they range from good to really, really good. If you see a big hunk of meat on a spit near the entrance, just go in and order a couple of tacos pastor (they will probably cost about $0.75 each.) We had a lot of these, but the best we had were at LaAutentica Antigua in Condesa (can't find a webpage or map listing, but I *think* it is on one of the side streets just to the north of the 5-point intersection of Michoacan, Suarez, and Altixco that is surrounded by restaurants and bars.) Another great spot where the tortas are gigantic and delicious is the collection of food stands in Chapultapec Park.

But seriously, it is pretty hard to go wrong eating at any of these places as far as I can tell. This made up the majority of our food consumption (and stretched our traveldollars pesos rather nicely.)

There are a lot of fancy restaurants in Polanco, the upscale neighborhood where you will find international 4- and 5-star hotels and wealthy tourists. I am sure that many of them produce excellent food. We ate at one of them, which I will not name because I really have no desire to trash them (they delivered exactly what they promised, well, and the service--while a bit overly fussy for my tastes--was excellent.)

My beef is that I've had essentially the same genre of food, slightly better--and less expensive--in several restaurants in Tucson, and particularly at Cafe Poca Cosa. This suggests to me that high-end Mexican can only be so good, and I might have had it already. Good to know...back to the taqueria we go...

On our last night, however, we did treat ourselves to the more affordable (but still a bit pricy by Mexico City standards) La Tecla in Roma. This was excellent, and I would rank it among my favorite dining experiences in Paris, Saigon, Hanoi, Chicago, etc., etc. We had a tostada with sashimi-grade tuna, caramelized onion, and chipotle mayonnaise that was to die for. I had a steak with twin sauces of stilton and huitlacoche (don't knock it till you've tried it), and M had a fish dish; both were solid. Dessert (which I didn't even bother ordering at the other place) was an impossibly airy flan with cajeta sauce and a boozy crepe dish with a bunch of berries set on fire at some point. Awesome.

Cantinas

The cantina is probably the thing that your "standard" Mexican restaurant in the US is most trying to recreate--casual places with big tables, wandering mariachis, reasonably priced food, and they don't mind if you linger for hours playing dominoes and drinking beer. However, you are unlikely to hear the words "careful, hot plate!" and not everything comes entombed in processed cheese.

We ate at two cantinas--one of which I cannot recall the name of, but it is the one the southeast corner of Obregon and Cuauhtemoc [Ed: per my wife it is called La Autentica]--and at El Centenario near the heart of the Condesa neighborhood. But the one we really loved was La Opera between the Zocalo and the Alameda. (We just had drinks there.) That place was like stepping back in time.

Tacos and tortas

You can't go far in Mexico City without tripping over a small place that sells tacos and/or tortas (usually both). As far as I can tell, they range from good to really, really good. If you see a big hunk of meat on a spit near the entrance, just go in and order a couple of tacos pastor (they will probably cost about $0.75 each.) We had a lot of these, but the best we had were at La

But seriously, it is pretty hard to go wrong eating at any of these places as far as I can tell. This made up the majority of our food consumption (and stretched our travel

1.07.2013

if kristol is agin' it...

I'm for it.

(Why anyone listens to a single thing that amoral chickenhawk fuckwit has to say is beyond me.)

(Why anyone listens to a single thing that amoral chickenhawk fuckwit has to say is beyond me.)

1.04.2013

back to life, back to reality

I have some thoughts I'd like to get down about our time in Mexico, which I hope to flesh out in the next week or so once I get a few more pressing items squared away. But here are a few highlights:

--Mexico City exceeded my expectations, by quite a lot. I found it (or rather, the central part of the megalopolis in which we spent nearly all of our time, which is still rather large in and of itself) to be clean, safe, relatively easy to navigate, and all around really pleasant and fun. Caveats: I really like big cities, and I speak just enough Spanish to get by most of the time. (More on the latter point later.)

--If you like contemporary and/or modern art, you could easily spend a week in Mexico City doing little else.

--Fancy restaurants in Mexico City are for suckers. The most expensive meal we had there wasn't even the 5th best. (I will have a great deal more to say about food.)

--Speaking of food, Oaxaca should be on every food lover's list. Less of a taco and torta town than Mexico City, it's mostly about mole, Oaxacan cheese, and tamales. I had a plate of enchilladas with mole rojo that is among the best things I've ever tasted, anywhere. Seriously.

--There are a lot of tourists in Oaxaca, but most of them are Mexican.

--Turns out I really like mezcal. A lot.

--There are a LOT of police in Oaxaca city. More per capita (at least visibly) than I've seen anywhere else I've been. I suspect that this has more to do with the recent history of civil unrest than with the drug war, but I haven't really had a chance to look into that. In any case, it felt very secure, though it was kind of surreal to see a minor scuffle on the Zocalo elicit a response of approximately 100 officers.

--The people with whom we interacted (with exactly one exception) could not have been more friendly, hospitable, generous, and patient with our limited language skills.

--Mexico City exceeded my expectations, by quite a lot. I found it (or rather, the central part of the megalopolis in which we spent nearly all of our time, which is still rather large in and of itself) to be clean, safe, relatively easy to navigate, and all around really pleasant and fun. Caveats: I really like big cities, and I speak just enough Spanish to get by most of the time. (More on the latter point later.)

--If you like contemporary and/or modern art, you could easily spend a week in Mexico City doing little else.

--Fancy restaurants in Mexico City are for suckers. The most expensive meal we had there wasn't even the 5th best. (I will have a great deal more to say about food.)

--Speaking of food, Oaxaca should be on every food lover's list. Less of a taco and torta town than Mexico City, it's mostly about mole, Oaxacan cheese, and tamales. I had a plate of enchilladas with mole rojo that is among the best things I've ever tasted, anywhere. Seriously.

--There are a lot of tourists in Oaxaca, but most of them are Mexican.

--Turns out I really like mezcal. A lot.

--There are a LOT of police in Oaxaca city. More per capita (at least visibly) than I've seen anywhere else I've been. I suspect that this has more to do with the recent history of civil unrest than with the drug war, but I haven't really had a chance to look into that. In any case, it felt very secure, though it was kind of surreal to see a minor scuffle on the Zocalo elicit a response of approximately 100 officers.

--The people with whom we interacted (with exactly one exception) could not have been more friendly, hospitable, generous, and patient with our limited language skills.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)